The Smith family in front of the family home on the Boyd farm, which was recently honored for a Hoosier Homestead award. Pictured: Kelly Cochran, sister, Debra Smith, with husband Clark Smith and their daughter Caroline Smith. Thursday, April 7, 2022.

Tom Russo | Daily Reporter

HANCOCK COUNTY — Debra Smith was brushing her teeth in her farmhouse north of Greenfield on a recent evening when she heard a cow bawling out in the pasture.

“That’s not right,” she remembered thinking. “Something’s wrong.”

She headed out to find that it was a heifer giving birth to her first calf. Smith realized she needed reinforcements. Fortunately she had plenty of family visiting to come to her aid, including her mother, Kay Boyd.

“It had tumbled into the mud with all the rain we’ve had,” Boyd recalled of the calf.

They got the newborn onto a sled and transported it to dry ground.

“We got the baby calf out of the mud and up where it could stand and start nursing,” Smith said. “It’s up and doing well and running around.”

The farm has captured moments like these for over 170 years now, across seven generations of the same family. That family was recently among those recognized with a Hoosier Homestead Award from the Indiana State Department of Agriculture, which honors longstanding commitments to farming across the state.

The family received a Sesquicentennial Hoosier Homestead Award celebrating at least 150 years of existence.

Boyd’s great-great-grandfather, Philander Boyd, a prominent Greenfield businessman, bought the farm in 1851 on Ind. 9 just north of Greenfield. She was surprised to learn the transfer occurred on Dec. 25.

“What a Christmas present,” she said.

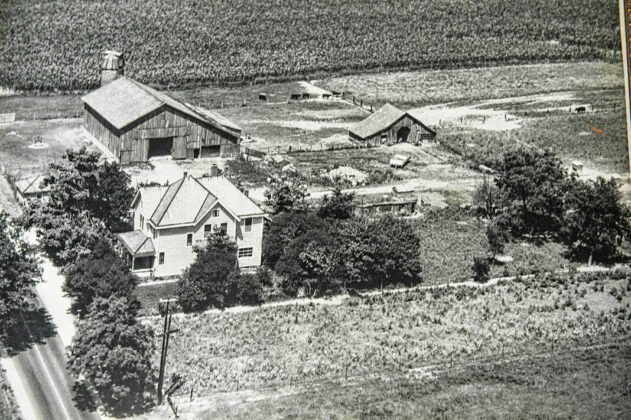

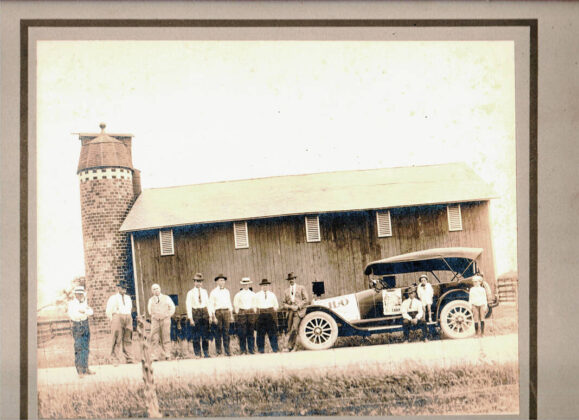

A large barn on the property made with large beams and pegs instead of nails, a photo of which appears to be dated either 1853 or 1858, still has its original slate roof.

Philander’s son, Peter, lived on the farm and raised his family there. Then Peter’s son, Walter, whose journals still remain in the family and recount tasks like clearing timber from the land.

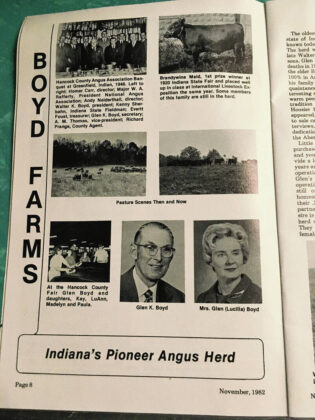

“When his first daughter was born, in 1904, he went out and celebrated by buying an Angus cow,” Boyd said of Walter, her grandfather. “And that became the foundation of Boyd Farms Angus. It’s one of the original pioneer herds in the state of Indiana, and it’s still in existence today.”

Walter and his wife, Kate, had several other children, including a son named Glen. He and his wife, Lucilla, had four daughters, one of whom is Kay Boyd.

Boyd has two daughters. Debra Smith lives on the farm with her husband, Clark, and their 8-month-old daughter, Caroline Lucilla.

When Smith isn’t helping rescue newborn calves from muddy pasture, she serves as the executive director of Greenfield Main Street.

Boyd’s daughter, Kelly Cochran, is a pharmacist by day and helps with the farm’s cattle.

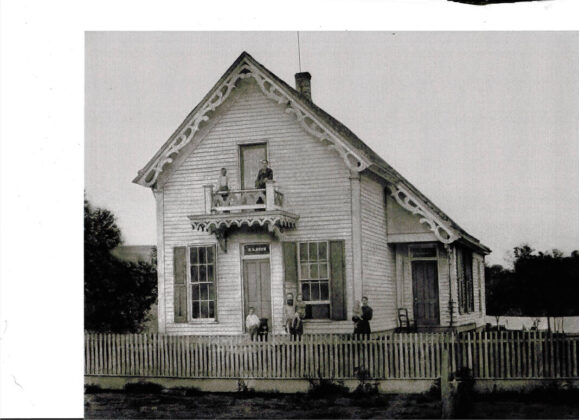

Smith and her family live in the farm’s original home that’s been updated over the decades.

Along with its cattle herd, the farm also raises corn, soybeans and hay, which Joe and Pat Mohr and their families help with.

Boyd, a veterinarian who lives on a farm in Kentland in northwestern Indiana with her husband, Frank Terrell, grew up on her family’s Hancock County farm and saw the profession change a lot over the years. Her father used draft horses to work the fields. When she was growing up, it was tractors.

“Now, when the Mohr family farms, they’ve got huge equipment that run with computers and all that fancy stuff,” she said. “It has changed quite a bit.”

She remembers her parents, especially her father, having grown up locally, stressing the importance of contributing to the community over the decades.

“I’m proud to continue that tradition and have my family contribute and to live in the community and be involved in not only church, but philanthropic organizations,” Boyd said.

Her sisters, Paula Holbrook and LuAnn Durham, both of North Carolina, and Madelyn Stanforth of Kokomo, retain ownership of some of the farm ground as well.

Smith grew up on her family’s farm in Kentland and visited the Hancock County farm often growing up. She has fond memories of spending time with her late grandmother, Lucilla, the grandeur of the home and how it served as a gathering place for extended family. Visits were filled with American Girl Doll tea parties and treks to the part of Brandywine Creek that winds through the property.

“It was really like a second home to me,” Smith said.

She moved to Greenfield about seven years ago. Her grandmother had moved into an assisted living facility, and it made sense for Smith to rent the farmhouse, which she initially planned to be on an interim basis.

“I decided I wanted to be more involved in the community, and that’s why I took the position with Greenfield Main Street,” she said.

Until moving onto the farm, she never realized how many people took a protective concern for the property. It’s not uncommon for her to receive phone calls when something may appear to be wrong with a cow, or if one gets into an area they shouldn’t be in.

“It’s almost like they have a vested interest in it as well because they drive by it every day, whether it’s on their way home, or on their way to work, and they get to see the cattle and the home, and especially now in calving season we have a bunch of baby calves running around,” Smith said. “There’s just a lot of people that keep an eye on it in their own way that I wasn’t aware of that I’ve really come to appreciate.”

Boyd is proud of the farm being able to stay in the family after all these years, and hopes to see it continue to do so.

“My hope is to continue that legacy as well,” Smith said.

At the same time, they realize the surrounding area is far different from the days Philander Boyd first staked his claim.

“There’s a lot of fear with the growth and development of Greenfield,” Smith said. “Obviously nobody can take the land from us, but they can build up around it and change the scenery and landscape to make it just not as enjoyable, and that’s one of my fears is seeing all the development and making sure that it’s done in a strategic way that doesn’t endanger the beauty of the farmland and our home. It’s important to value farmland because once we put something there, it’s a lot harder to take it away.”

She finds comfort in the enduring passion for agriculture from her husband, Clark, who grew up on a farm, and her sister, Kelly, who did as well and often visits to help.

“I think having a united front in the next generation that still wants that kind of a lifestyle and values that is really important to make sure that it does carry on,” Smith said.

The family was one of 69 Indiana farms and their farming families to whom the state department of agriculture awarded Hoosier Homestead Awards.

To be named a Hoosier Homestead, farms must be owned by the same family for more than 100 consecutive years and consist of more than 20 acres. If less than 20 acres, the farm must produce more than $1,000 of agricultural products per year. Indiana farms may qualify for three honors: Centennial Award for 100 years of ownership, Sesquicentennial Award for 150 years of ownership and the Bicentennial Award for 200 years of ownership.